This is one story in a series of stories about Cuba. Images from this story are also available in my gallery.

“In this series of images, I chose black and white to draw attention to the form, craft, and physicality of the work. In a space stripped of color, the tools and gestures become the story.”

Inside a small, sweltering foundry, a handful of men craft marine propellers using the same methods and tools from half a century ago — bare-skinned, unmasked, and years past the health limit meant to protect them. It’s not progress. It’s survival in a place where safety rules are a rumor and the work never changes.

—

A Furnace Behind Bars

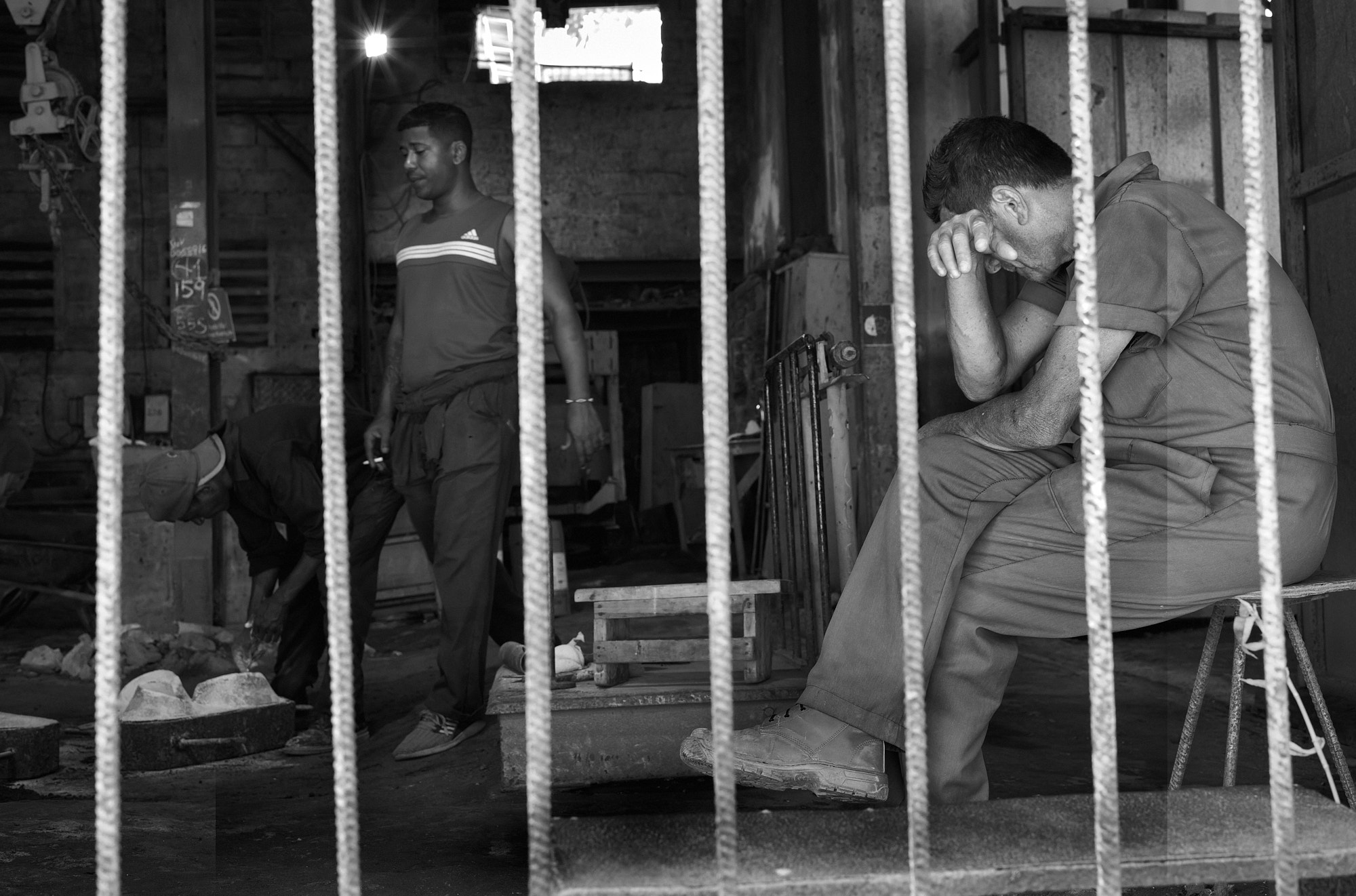

This was the scene I arrived to: a man behind bars, half-lit by the open gate. Palacios, 59, wore torn street clothes. My fixer quietly remarked, “He probably doesn’t have a wife — no one to patch the holes, and it’s unusual he is not wearing a uniform.” That comment stuck longer than I expected.

This place was discovered accidentally, but I should have known from the rusted gate and barred windows: this wasn’t going to be an ordinary workshop. Three men were inside — laughing, drinking, sweating through ripped clothes — behind them, it looked more like a prison foundry than a functioning shop. Maybe that was the point. A workplace becomes a cage if you stop dreaming.

—

Hands and Heat

Crouched in the dirt, I peered through the low bars bolted to the building — the only way to see inside. We weren’t allowed in; officially, we weren’t supposed to be there at all. In Cuba, government facilities are off limits to me. Doors stay closed for reasons you don’t ask about.

Here Denis, 49, meticulously packs sand into a mold — by hand. He’s been doing this for 25 years. No gloves. No mask. The process looks like something out of a 1930s industrial archive.

And outside the cage, while I was kneeling to take these images, my knees became filthy due to the oil that was had seeped and soaked into the ground over the decades of that shops is existence.

The casting floor is soaked with decades of oil, the same substance that soaked into my pants. That oil, that heat, those fumes, they seep into your skin. There’s no protection. And no pretense of safety.

The casting floor is soaked with decades of oil, the same substance that soaked into my pants. That oil, that heat, those fumes, they seep into your skin. There’s no protection. And no pretense of safety. The workers handle sand loaded with crystalline silica and stand over molten metal that emits toxic fumes, all without goggles, respirators, or gloves. 1 2 3 Toxins like lead, nickel, and PAHs can be inhaled or absorbed through skin, especially in heat and sweat.4 5

Palacios has worked here for 18 years; Denis, for 25. They told us a “10-year limit” was supposed to exist — perhaps a symbolic guideline, as I found no record of any official Cuban regulation. Even so, without protective gear, every year here is dangerous. In fact, even 10 years under these conditions could result in health issues.6 The group knew it — and laughed when they mentioned the supposed limit. “A joke,” one said.

—

The Vodka Break

Palacios left while we were there, mid-morning, and returned with a bottle of vodka, holding it up like a trophy. The men drank and laughed, filling their classes as they worked.

There’s something deeply sad at that moment — a man toasts his friends with the same hand he uses to pour molten metal. Celebration? Yes. But mostly sedation.

—

Side Jobs and Silent Deals

They don’t just build propellers. They build other parts, on the side, using government machines and materials, an unspoken side hustles to survive. Everyone knows. No one interferes.

Here Denis displays for form making process while Tomayo (31 years old) looks on. I can see they take pride in their work, but Palacios states they must do well due to lack of other work options.

We were photographing when someone said, “The boss is coming.” My fixer and I came up with a plan: run in opposite directions. That’s what it means to document decay in Cuba. It’s not just about access — it’s about fear. This is true for schools and hospitals as well.

Turns out, the boss didn’t care. He sat down, watched us, and started venting about his kid who has blood in the urine, stomach pain. The hospital couldn’t help. But a friend of the boss could pull strings and find test materials.

In Cuba, even medicine has a grey market. Even a manager who lets his workers drink openly needs to hustle to care for his child.

—

Cages, Real and Imagined

We shot from outside the iron bars. The men didn’t stop or hide anything. Not the vodka. Not the grime. Not the broken safety protocol. It was like they knew nothing could make their situation worse… or better.

Palacios said it out loud: “I hate the nepotism of the Castro family.” But he comes back every day. Maybe it’s safer inside the cage. Maybe the idea of leaving is more terrifying than staying.

—

Conclusion: What’s Worse Than a Prison?

A prison without a guard. A cell with the door left open — and nobody leaves.

These men have skills. They could maybe go work in private business. They could maybe leave. But they don’t. Maybe because they can’t. Or maybe because they’ve forgotten how to want more.

They drink. They laugh. They survive. But they don’t dream.

—

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), “Controlling Silica Dust from Foundry Casting-Cleaning Operations”: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/hazardcontrol/hc23.html ↩

- “Characteristics and occupational risk assessment of occupational silica-dust and noise exposure in ferrous metal foundries in Ningbo, China”: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9947523/ ↩

- UK HSE “Health risks in the molten metal industries”: https://www.hse.gov.uk/moltenmetals/health-topics.htm ↩

- CDC – About Skin Exposures and Effects: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/skin/skinnotation_profiles.html ↩

- ATSDR – PAHs Toxicology: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxfaqs/tfacts69.pdf ↩

- Galfand Berger LLP “What Are the Hazards of Metal Casting?“ https://www.galfandberger.com/2021/11/03/hazards-metal-casting/ ↩

Leave a comment