This is the first in a series of stories about Cuba.

Smuggling the Truth

I am at the airport going home. After three exhausting weeks in Cuba documenting this country with over 70 pages of interview notes and 5000 images, the final hurdle is before me: I am in line for customs.

There is confusion ahead of me. Cuban officials are pulling people out of line and going into adjacent rooms. But I had prepared for this: All of my images and scanned notes are backed up on two drives, and these are hidden in photo equipment.

The journalist notepads I used for interviews? Last night at dinner, I disguised them—made them look like part of a movie project supposedly set in New York. My alibi: the notes are for a fictional script, inspired by the rich color of this country.

I just had to be calm for 20 more minutes.

Am I being paranoid?

My fixer had warned me, over and over, about the danger of the interviews. He didn’t know the depth I’d go to before we started. I thought he was being dramatic.

But over those three weeks, I met prominent people, people with stories to tell, who refused to be interviewed out of fear.

And then I met Lily.

We discussed her medical trauma, politics, the past, and the future of Cuba in over 90 minutes of discussion. From her story:

”People are afraid.” She says. “I am afraid to talk to you about this. The government tells to the world a different story than what’s actually going on here. The police may come and are aggressive”.

And with her words, I finally got the seriousness of what I was doing. It clicked. And I feel sick to my stomach.

I wasn’t just taking pictures. I was collecting fragments of people’s lives. Their fears. Their faith. Their broken dreams and fierce pride.

Why Me? Why Now?

The desire to travel and document people as a photojournalist or documentary photographer has been in me for as long as I can remember. But family, work, and kids—happily—put that dream on the side burner.

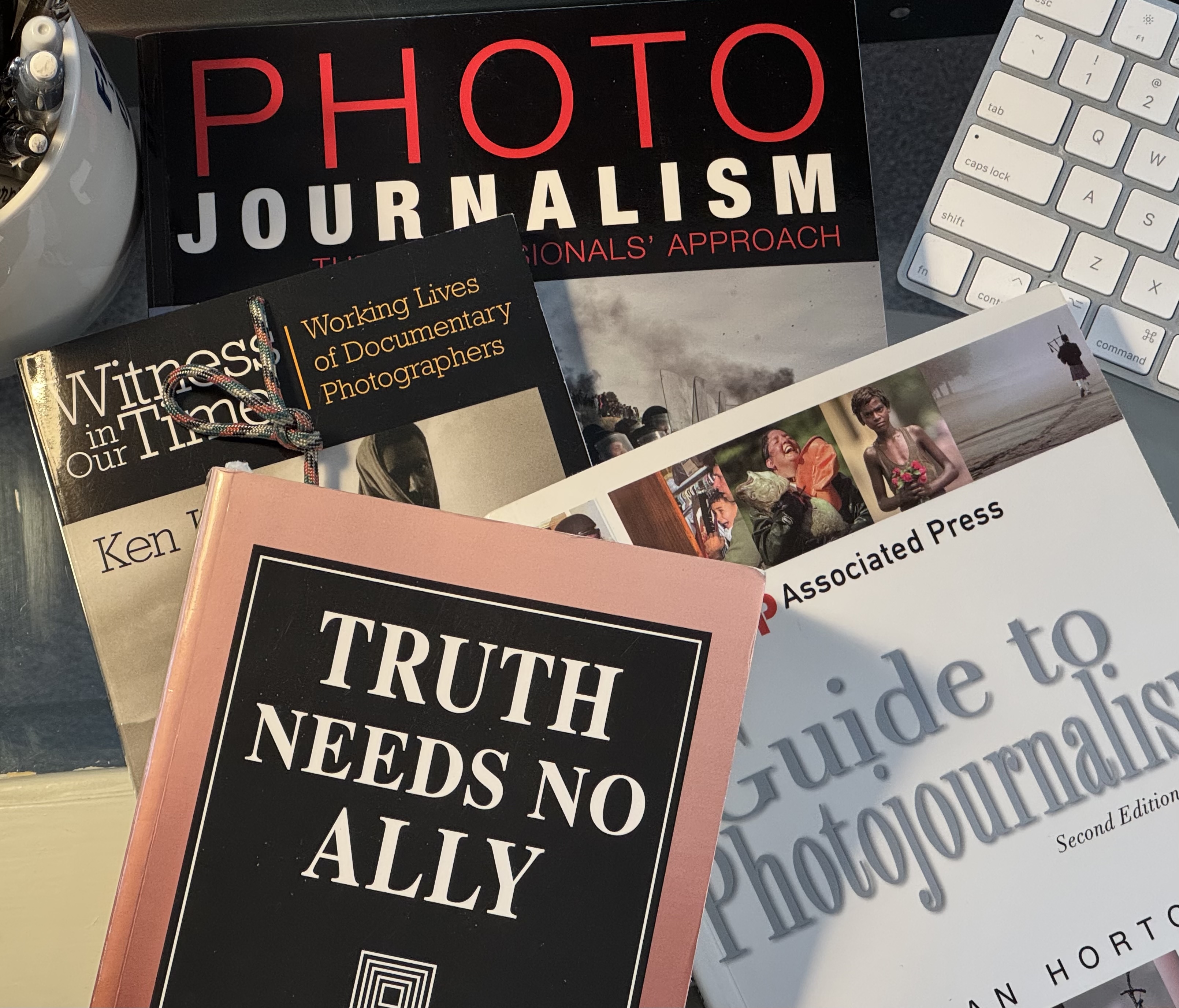

Over the years, I bought and read many books on photojournalism and documentary photography: Truth Needs No Ally, Witness in Our Time, Photojournalism—The Professional’s Approach, AP’s Guide to Photojournalism…

Time passed. The kids grew up. Careers advanced.

While rereading Truth Needs No Ally at the end of last year, I came across a mention of a working photojournalist. Curious, I visited his website—and saw that he offered workshops. What a mentor he might be, I thought, to learn how to better photograph in that style. Paris was an option. But so was Cuba.

Cuba.

I’ve long been curious about that place. My mom had traveled there before the revolution and spoke fondly of it as I was growing up. A place steeped in political controversy. Loved and hated here in the States. Mysterious. Raw. The kind of place I’ve always wanted to document. Could this be the catalyst that finally propels me towards a documentary photography career, given my commercial photography work?

The workshop would only be one week.

But I’ve traveled enough to know better by now. What I’ve learned, often the hard way, is that if you’re going to go, go all in. Spend time. Have no regrets. I still carry one from 2023: I was in Israel and wanted to visit and photograph Gaza. But I let the logistics and noise get in the way. That will always sit heavy with me.

So how do I do this right?

Retirement was already available—just waiting for the right moment. The calculus formed: Retire. Plan. Do the trip. Come back and do the work of spending weeks of editing, writing, shaping the story. Then publish the work. I knew from those books: That’s what it takes if you want to do this seriously. That’s what I’ve started now.

What I Was Really After

This project isn’t about old cars or faded paint. It’s about resilience, contradiction, and survival. It’s about the tension between what people endure and what they believe. I didn’t just document scenery — I documented people: their fears, their hopes, their losses, and their ingenious workarounds for a system that often fails them.

I hope this helps others see how individual struggles are connected to larger policies and systems, both inside and outside the country.

Through these interviews, I’m trying to understand where Cuba is today and how it got here. Each one added a personal perspective on daily life that is shaped by resilience, hardship, and history.

Method

I spent three weeks in Cuba — the first in the photo workshop, the next two with a local fixer who helped me go far off the tourist track.

Before I arrived, I spent two months studying, planning themes, researching history, identifying potential interview subjects with my fixer, and mapping logistics. In the end, I shot over 5,000 images and conducted more than 14 interviews, from spontaneous encounters to carefully arranged conversations.

After returning home, the process continued. I went back through every note, expanded on key points with more in-depth research, and began tagging common themes.

This isn’t a collection of random snapshots. This is a structured narrative. Using keywords with data graphs, I’m tracking ideas that repeat and thread through these lives, showing patterns that hint at deeper truths.

What You’ll See — And What You Won’t

Every post you’ll read is grounded in a real person. A real moment. A real story.

Each blog entry will dive into individual lives while surfacing larger themes — scarcity, resilience, corruption, hope.

These posts won’t be comfortable. Some will challenge assumptions. Some will sting. But all of them will show Cuba in a way you likely haven’t seen before: raw, nuanced, and human.

If You’re Still Reading, This is for You

The images and captions above are only glimpses—snapshots of lives I’ll explore in depth in the posts that follow. If something here made you pause, stay with me. Subscribe, follow, come back. I’ll be posting regularly, each story unfolding piece by piece. There’s a rhythm to this project, a heartbeat that begins here. And if you stay with it, I believe it will change how you see Cuba.

Leave a comment